A personal look at community and intimacy in urban landscapes through the lens of Wong Kar Wei’s cinematography, specifically the masterful Chungking Express.

Ever felt too small in the big city? Too crowded to form your own identity? Or perhaps for you, you felt safety, knowing there were at least a thousand other people – living on top or below – the few square meters you’ve called home, that were experiencing the same things you were. Perhaps you felt a kind of social satisfaction, your faceless neighbours surrounding you, living their lives parallelly yet never intersecting with yours.

You’ve maybe even made up your own names and stories for them, never once actually asking Ben who gets off at floor seven why he plays Sting’s ‘That’s not the Shape of my Heart’ on a two-hour loop fortnightly on a Friday, or even if his name is Ben – seems too personal. These details are irrelevant anyway, there’s much more of interest to know about him. That his favourite flavour of crisp is sweet chilli, of which he enjoys Tyrells the most, this will tell you all you need to know about which tax bracket he’s in. That he calls his mum before work most mornings, always ending the conversation with a “yes mum, I’ll be married soon.” This at first comes as a massive shock, for Ben, more often than not, is seen with new god-like woman on his arm every weekend. A plethora of women whose beauty is so striking, men would have gone to war for them.

Throughout the years you have shared space together with Ben, the volume of his nose canal has decreased dramatically. Especially these past few months that you’ve found (through eavesdropping his many phone calls) he’s setting up his own company, the stress quite evidently getting to him. Despite all this grandeur, you get the distinct impression he cries himself to sleep most nights. He leaves tell-tell signs of his unhappiness wherever he walks. His friends, superficial; his eating habits, concerning; his eyes, withdrawn. Whether knowledge of his tears comes from you excellent analysis of human behaviour, or the fact that when the Sting fades, you can hear sobbing: is irrelevant. Rather your satisfaction proves more complex than just a pat on the back for your excellent powers of deduction. It comes from a place, maybe to your surprise, much deeper than that. You both have, to a certain extent, shared a life together. These fleeting moments of intimacy has turned him into a comforting presence. You feel as if you know Ben most of all right now and the thought of that, brings you peace? His presence brings an ambivalent dream like quality to your life. Romanticising him gives you a sense of importance.

“In this life I do your nails, but in a past life I’d like to think you did mine,” is what my nail technician tells me one Thursday afternoon. It gets me thinking. The day before I had watched Celine Song’s 2023 film, Past Lives. It discussed the ancient Korean concept of inyeon, “It means providence or fate. But it’s specifically about relationships between people.” Is how it’s described by the films protagonist. Although, inyeon is a strictly Korean word, the concept is a relatively global one. In Turkey, there is kismet. In Buddhism, people can share karma. In modern times we especially gravitate towards these concepts. This contemporary infatuation can be considered bizarre. Organised religion is on the decline, personal spirituality on the rise.

Globalization probably has something to do with that. In the case of big cities, connection, is a big problem. Our increasingly individualistic style of living doesn’t make room for this kind of providence anymore, and yet we compensate for it. Imagining some kind of fated red string tying us to people we barley even utter hello at.

The bigger our cities get, the more “we rub shoulders with each other every day. We may not know each other. But we could become good friends someday.”

This omniscient monologue is how Hong Kong director Wong Kar Wei begins his standout 1994 film Chungking Express. Police Officer Takeshi Kaneshiro, known as cop 223 laments over his recent break-up with his now ex-girlfriend. In the process of his mourning, he meets Bridgette Lin’s blonde wig character in a bar, who unknowingly to him, is a drug smuggler facing her own lamentations. His perception over loss changes upon sharing time with her. This story remains somewhat unfinished where it is suddenly interrupted by another. Spurred into centre stage by the brushing of shoulders with Faye Wong, we see her character young and somewhat lost – we’ve all been there, some of us still are – working in a fast-food chain store. We watch her budding relationship with another police officer known as cop 663, played by Tony Leung, who is also freshly thrust into singledom when his flight attendant girlfriend suddenly breaks-up with him. His perception over loss changes upon sharing space with her.

Romance has never looked so dreamy. But how does he do it, how does he create such a feeling of timelessness, nostalgia, and an intimacy so strong you feel the pangs of yearning yourself?

Time and Loneliness

What follows those first few lines of Chungking Express are a bombardment of flavours, saturated colours, and blurred movement. The camera shakes, the shots are often blurred and out of focus, the pan-in doesn’t always make sense. With all this we see the cinematography as painfully human. It acts as our eyes do, specific focuses on often inexplicable things coupled with blurring of quite important details. However, in the humanization of the camera it actually becomes a celebration of human limitations. For the cinematography none the less, is beautiful.

These imperfections are mostly achieved by cinematographer Christopher Doyle through step-printing technique. This is usually used on a specific moment. It forces you the audience, to let go of the objective reality of things and instead feel a moment. From up close the passage to time is painfully slow. When we look from further away, we instead become shocked at how fast things have rushed by us. This destruction of reality is actually what makes things more realistic to us.

This continues throughout the film and in particular we notice movement becomes our primary perception of time, for pasta never boils when we are looking. In this sense time is very subjective in Wong Kar Wei’s films. The characters always seem to be in pain. Their existence pains them. Their narration is mostly reflective but sometimes it acts as live commentary. Making them lost somewhere in between the past and the present, much like our own thoughts really. Everyone is within the same space, but they all seem to live in their own distinctly different times. This all adds to their own unbearable loneliness. Even when within each other presence, they live distinctly apart.

Space and Loneliness

Although there is a notable distinct lack of space in Chungking Express, the small spaces that are shared are heavily personified. This is achieved through time. We see the same space through many different times, in many varying circumstances. It makes us view the space differently. As well as these characters, these spaces too have lived many lives. They have born witness to many emotions and events. All this adds a specific colour to a space, guiding how we may feel about it. For don’t we all have our favourite depression spot? Mine is the upper deck of the 319 bus, it has witnessed too many of my tears for it to not earn that title.

In Chungking Express especially, specific locations bear no real meaning. Meaning is created when there are people to share space with, i.e. the fast-food restaurant.

The space that characters inhabit in relation to each other is also an important detail. You’ll notice in many of his films, we get regular close up of characters’ eyes. What is interesting still, is that these characters are usually filmed alone, even when in conversation or joined by someone else. Even when the camera chooses to place two people on screen together, their eye contact is always broken by the end of a scene. Usually after them walking away from each other. This all adds to this feeling of lost intimacy. Sharing space but feeling alone.

Chungking Express

We discuss these concepts because they are crucial to how we experience the film. The first story in Chungking Express is about time, the second is about space.

In the first story, the two leads meet as a result of accidental timing. They both have past demons they wish to forget, and they do so, in each other. The result of their condition keeps them together.

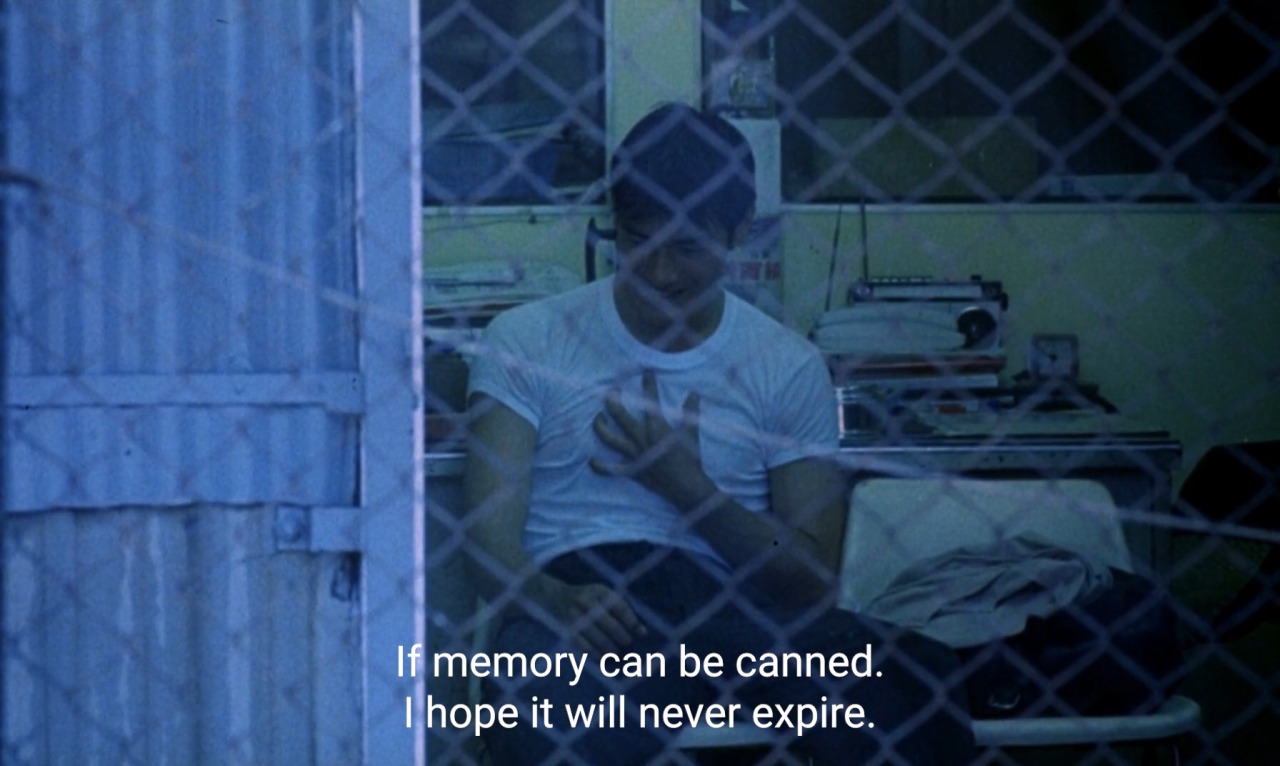

Cop 223 becomes quite obsessed with the idea of May 1st, for his girlfriend – also aptly called May – brakes up with him on April fool’s day. He waits in the hope that it is one big April fool’s joke until May 1st, at which point his compounded grief at losing her hits him all at once. Pineapple cans become a clever metaphor for expiration of feelings. For whom is it that hasn’t at least once had to reckon with the notion that feelings are a lot less constant and a lot more fleeting than we like to believe?

At this point is where he meets Bridgette Lin’s Blond wig character. We see a much more fragmented version of her story. There are hints of a break-up, as well as wanting to forget her current reality. They are exactly what the other needs at that moment and the perfection of their timing results in an incredibly cathartic experience for both characters. The perfection of timing is also what makes their meeting so impactful.

In the second story, the two leads meet as a result of repetitively sharing space. As such, their initial few meetings don’t have that same grand impression. One works at the fast-food store; another frequents it. There is not enough space for someone new in cop 663’s life while someone else is occupying that space. So, in this case, the result of their condition keeps them apart. This may sound counter intuitive, since Faye clearly likes the cop. However, it isn’t necessarily the cop she likes as much as the idea he presents to her. She likes to think of herself as the one who has a space in his space.

What is interesting is when Faye Wong starts removing traces of the police officers former partner – unceremoniously from his apartment – and instead planting traces of herself, while at first the cop doesn’t notice, slowly he too begins to move on. He starts thinking of new dreams, and new people. When this happens, he begins to live his reality as opposed to his dreams. His reality is decidedly more difficult, he must be vulnerable, open to being rejected again. Yet, he faces it.

The tension of this story forms in their disparity of timing. The cop is now in reality, but Faye is still living in a dream. She still dreams of California, and a life outside this shop. While one is ready for a new love story, the other is not. It is only once Faye has realised some semblance of her dream – becoming a flight attendant and visiting California – that she becomes ready to face her own reality. Fortunately for her, the cop is waiting, and in the same space they shared. Wong Kar Wei is a romantic after all.

Chungking Express, You and Me

The film ends with the lines shared by the cop and Faye where Faye asks, “Where shall we go?” to which the cop replies “Wherever, if with you.” With these lines all the themes that we have previously discussed are rendered lacking. For in those final lines the real theme of the film becomes clear. It’s about you. It’s about how you perceive time. It’s about how you feel about space. It’s about your dreams, your reality and everything that may lie in-between that for you. The film invites you to live authentically for yourself.

In all my years of cinema going – for I am a veteran – I have never been so touched by a film. For most of my, somewhat limited, life; I have spent a lot of time feeling quite distant from it. It was not that I considered myself an outsider of sorts, I could just never be close enough to the people within my life in the way that made me feel whole; I yearned for everything. Every mishap, every minor detail, every minute thought ever had. But, in an age of ultra-individualism this was, and still is, impossible. The effect Chungking Express had on me was colossal. It captured feelings within me I hadn’t ever been able to express. It wasn’t just about a distant sense of dissatisfaction, or a yearning for something I have never been able to name, or that even that when I am surrounded by so many people, still, I manage to feel alone. The kind of alone that made inanimate objects, like my bar of soap and my favourite towel, my best friends. It’s more that the film made me feel seen, in a way I hadn’t ever been, and it changed the trajectory of my life. I felt born the day I watched that film.

Nietzsche once said “Men fall into two groups: slaves and free men. Whoever does not have two-thirds of his day for himself, is a slave, whatever he may be: a statesman, a businessman, an official, or a scholar. Almost 100 years later, the same still applies. Our jobs rule our life. We do not slow down and think about what we do and why we do it. We often don’t have the time or financial freedom to. Yet I invite you. Look realistically at yourself, not your social circle – leave your comparisons at the door – but yourself. What makes you happy? What brings you joy? Do you live in a way that affords you that happiness, that joy?

Do we perhaps romanticise yearning? We are content in living in different spaces and different times, but what do we do to bridge that gap? Do we ever examine our own misery and ask ourselves: how did we end up here?

What particularly interested me is where my dissatisfaction at my own life came from? Why no matter how hard I tried was I always in some way lonely? Once I realised it wasn’t just me, for clearly Wong Kar Wei had also felt like me at some point. I felt the urgent need to unpack these feelings of mine.

I wanted to heal my relationship with space, time, and perception; and in that process heal the relationship I had with the world around me. I now understood, and more importantly, believed that we all felt the same hollowness, others just concealed it better than me. I knew my high-flying software engineering job was my parents dream and not mine, so I quit. I am on my way to pursue something more aligned to me. I knew my friends constant nagging for my lack of love life most likely reflected their priories on intimacy and not mine, so I asked them to stop. I deleted hinge, the desperation to find ‘the one’ in your 20s is not a rat race I think healthy to participate in.

I felt inspired to know those I brushed shoulders with. Intimacy comes in many forms, and small talk can be just as valuable as a ‘deep meaningful conversation’. Something my generation often does not prioritise.

I have since spoken to my neighbour Ben, whose name you may be surprised to find, is not Ben. He started out as a trader for some unbecoming investment bank, and now has his own company trading meme coins. In some ways, he’s as you’d expect, a big sleaze full of mostly empty compliments. In other ways, not so much. He was the sign interpreter for Eurovision a few years back. Clips he had sacramentally stored were happily shared with me over a tea on floor 7. His younger brother is deaf, and Ben believes enjoying music is a fundamental human right. I am glad to have spoken to him. In knowing him I understand myself better, and quite honestly: he has given me an endless supply of quick wit and biting remarks to adopt into my own vernacular.

There is nothing wrong with yearning for intimacy. But there is a case to be made for how unhealthy it is to think of some intimacy as cheap and others as rich. Each interaction is a blessing. It is special and it is important. It is up to us to be an active member in our communities. I do not say this to berate myself, rather, I mean this as plea to myself. Stop letting an abstract sense of shame stop me from acting in the way that makes me whole. Ultimately, the film is about me and so I should honour who I am. Then, why yearn when you can speak?